screenshot

screenshot

Mickey Z. -- World News Trust

Sept. 7, 2020

Discussions of suicide and violent death to follow.

***

“The trouble about jumping was that if you didn't pick the right number of stories, you might still be alive when you hit bottom.” (Sylvia Plath)

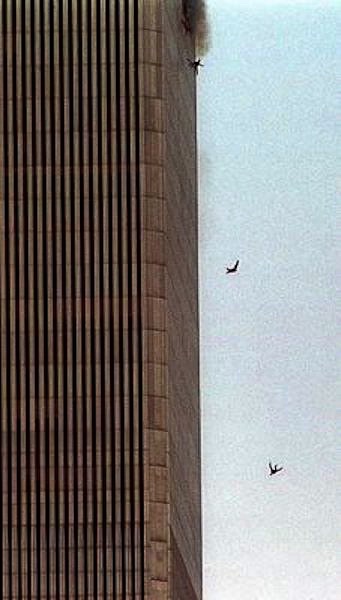

Nineteen years after the events of September 11, 2001, more than one thousand of the 2,753 victims in New York City have still not been identified from remains. We’ll never know the precise number but the most common estimate is that about 8 percent of those 2,753 souls died by jumping or falling out of the building windows.

screenshot

screenshot

Most call them the 9/11 jumpers. Others (strongly) beg to differ. Either way, their descent lasted about ten seconds, at a rate of 125 to 200 MPH. One of them landed on and killed a firefighter named Daniel Suhr — the first of 343 New York Fire Department casualties that day.

The initial jumper was spotted plummeting from the North Tower’s 93rd floor on the north face of the building — just 5 minutes after American Airlines Flight 11 struck at 8:46 AM.

The final leap occurred just seconds before the North Tower began collapsing at 10:28 AM.

It is believed only three people jumped or fell from the South Tower during the 102 minutes from the first jet strike to the second tower’s implosion.

It feels, to me, natural to wonder why some people jumped while others remained. It feels less natural to be highly invested in whether to label these victims “homicides” or “suicides.”

***

“The only difference between a suicide and a martyrdom is the amount of press coverage.” (Chuck Palahniuk)

Our school textbooks report with contempt on the Japanese kamikaze pilots of World War II. But the same historians swoon when recalling these words from Revolutionary War hero, Nathan Hale: “I only regret that I have but one life to give for my country.”

“Consider the man who straps a bomb to his chest and walks into a crowded market — we call him a ‘suicide bomber,’” states Margaret Battin, a professor of philosophy and internal medicine at the University of Utah. “Consider another man who falls on a grenade to save his buddy — we call him a ‘hero.’ The mechanism of death is the same — explosive injuries to the chest. But the intentions are very different.”

There is nothing uncomplicated about choosing to take one’s own life in any way, under any circumstances. I am certain that every person reading this article has been touched by suicide in one way or another. I know I have.

In the vast majority of cases, authorities and loved ones may look for any possible way to re-cast a possible suicide as an accident. We live in a culture that attaches an incredible amount of shame and stigma to self-inflicted death. Perhaps the only instance in which this determination is preferred is for those who accidentally perish during autoerotic asphyxiation.

It could be a suicide vest or a self-immolating monk, a physician-assisted suicide, or the Maccabees. Again, nothing about this topic is uncomplicated. But when as many as 200 people opt to plunge 1,100 to 1,300 feet to their death with the eyes on the world upon them, the complications multiply… and they persist.

screenshot

screenshot

The National Institute of Mental Health defines suicide as a “death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with intent to die as a result of the behavior.”

Some friends and family of the 9/11 jumpers aggressively push back at the suggestion any loved one of theirs would choose to leap rather than burn, asphyxiate, or go down with the buildings. It may run counter to their deeply held religious beliefs and therefore mean that this family member would be doomed to an eternity in Hell.

Others may view it as an act of cowardice, an “easy way out” — as if a restaurant worker or office administrative assistant was bound by some kind of soldier’s “code.”

Most famously, we have the provocative case of “Falling Man” — well-documented and worth reading about here.

In statistical terms, the 9/11 jumpers are treated no differently than anyone else who died in or around the towers that day. To call them suicides, it seems, is to question their courage. Even worse in post-9/11 America, it may be to equate their actions with those of the hijackers on the same day.

“To ask whether the 9/11 jumpers were suicides is to trade on the very negative connotations associated with the term suicide,” posits Margaret Battin, “and to imply that they did something wrong or perhaps even sinful.”

Ellen Borakove was a spokeswoman for the NYC medical examiner's office at the time. “A 'jumper' is somebody who goes to the office in the morning knowing that they will commit suicide,” she claimed. (I can only wonder if she’s ever considered, for example, the Wall Street workers who never imagined they’d be jumping from their office windows on the morning of Oct. 29, 1929 — the day of the Black Tuesday crash that precipitated the Great Depression.)

On the topic of 9/11 jumpers, Borakove stuck to the company line: “Jumping indicates a choice, and these people did not have that choice. That is why the deaths were ruled a homicide because the actions of other people caused them to die. The force of the explosion and the fire behind them forced them out of the windows.”

For some who fell, this may very well be true. Eyewitness Kelly Reyher worked on the 78th floor of the South Tower and, until his building was also hit, Reyher was able to watch — from his window just 120 feet away — people falling from the North Tower. He said some of them appeared “completely confused,” adding: “It looked like they were blinded by smoke and couldn’t breathe because their hands were over their faces. They would just walk to the edge where the jagged floor was and just fall out.”

Photo: Associated Press

Photo: Associated Press

For others, neither Borakove’s rationalization nor Reyher’s testimony feels adequate.

“I looked into my office and saw a gaping hole in the South side of WTC1 (North Tower),” Jonathan Weinberg would later write. Weinberg was on the 77th floor of the South Tower that day and adds: “We had no idea what had happened. No part of the plane was visible … At some point, I saw people appear at the edge of the gaping hole. Smoke was pouring out, and while I don't recall seeing much in the way of flames, it was clear that there was a raging fire going on inside the building. I saw a number of people jump to their death, desperate to get away from the heat and flames.”

Other witnesses saw at least four North Tower workers attempting to climb to windows on other floors to escape the heat, flames, and smoke. All four of them eventually lost their grip and fell.

And then we have the accounts of other jumpers who tried using drapes or tablecloths as makeshift parachutes — only to have these items instantly ripped from their hands from the sheer force of the fall.

Which of these cases qualify as “suicide” or “homicide” or “accident?” Why would any of us feel qualified to answer that question? Do these distinctions matter so much to some people because they’re being viewed through the lens of “us vs. them”? How open are we examining these questions with new eyes and an open mind?

***

public domain

public domain

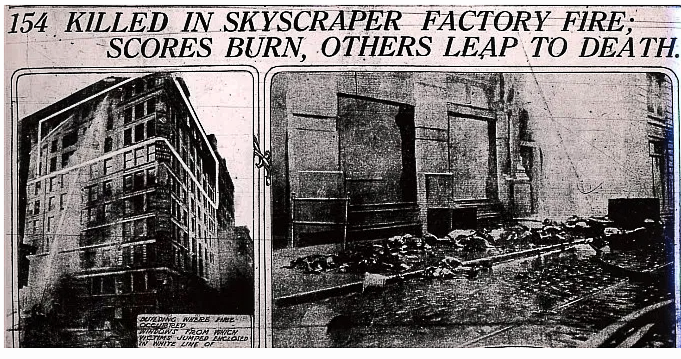

Experts who study such things claim that people will rarely throw themselves out of a burning building but one of NYC’s other most notorious fires challenges this narrative. During the Triangle Shirtwaist fire of 1911, 62 garment workers trapped on the top floors of the Asch Building either fell or chose to leap from the windows as the inferno accelerated.

Just how bad must it get, how hopeless must it feel, before someone makes a choice like this? Who are we to judge or categorize this decision?

Phone calls from inside the World Trade Center told stories of workers having to stand on desks because the floor was getting so hot. Combine that with the suffocating smoke. Combine that with the fact that they didn’t really know what had happened. Combine that with the jolting realization that no one was arriving to save them.

Voicemail messages included, “I’m sorry, we fought” and “I love you, Mom, I’m sorry” and simply, “I have to go.” Are these the last words of people who had just chosen how they would die? Again, we’ll never know. But do we have to know in order to feel profound compassion, sympathy, and grief?

“To be or not to be.”

Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 1

I personally knew three people who died at the WTC on 9/11 — two worked inside the buildings and one was a fireman. I don’t need to know the gruesome specifics of their demise to mourn and remember them. Their faces and stories stay with me. Their names are carved into official stone like all the rest.

public domain

public domain

Too many other names will not appear on lavish memorials or be recited aloud on any particular anniversary. No one will ever know how many humans had their lives cut short by “terrorism,” the “war on terrorism,” and all the myriad ancillary ways in which this particular expression of male violence claims its relentless collateral damage.

Meanwhile, suicide (in its officially acceptable form) is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States.

For those between the ages of 35 and 54, suicide is the fourth leading cause of death.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among individuals between 10 and 34.

In 2017, suicides outnumbered homicides in the United States by more than 2 to 1.

Since 2001, the suicide rate in America has increased by 31 percent.

Rather than engaging in a semantics battle about the patriotic integrity of a term, it feels more urgent to me that we begin addressing the ongoing, virtually invisible pandemic of suicide. As I touched on in an earlier article: if our way of life is so exemplary, why are more and more of us choosing death over it? And what can we do about the trend?

Ironically, September is Suicide Prevention Awareness Month.

The 9/11 jumpers faced a cruel, unimaginable choice and they are gone now for nearly two decades. Perhaps the best way to honor the nightmarish decision they were compelled to make on that sunny Tuesday morning is to do whatever we can — right now — to support anyone who may be feeling they have run out of options.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call the confidential, toll-free National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255). It’s available to everyone: 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

This article is written in memory of JT.

Suggested Reading: The Ethics of Suicide - Digital Archive

Mickey Z. can be found here. He is also the founder of Helping Homeless Women - NYC, offering direct relief to women on the streets of New York City. To help him grow this project, CLICK HERE and make a donation right now. And please spread the word!

Remembering the 9/11 Jumpers: When is a Suicide Not a Suicide? by Mickey Z. is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0