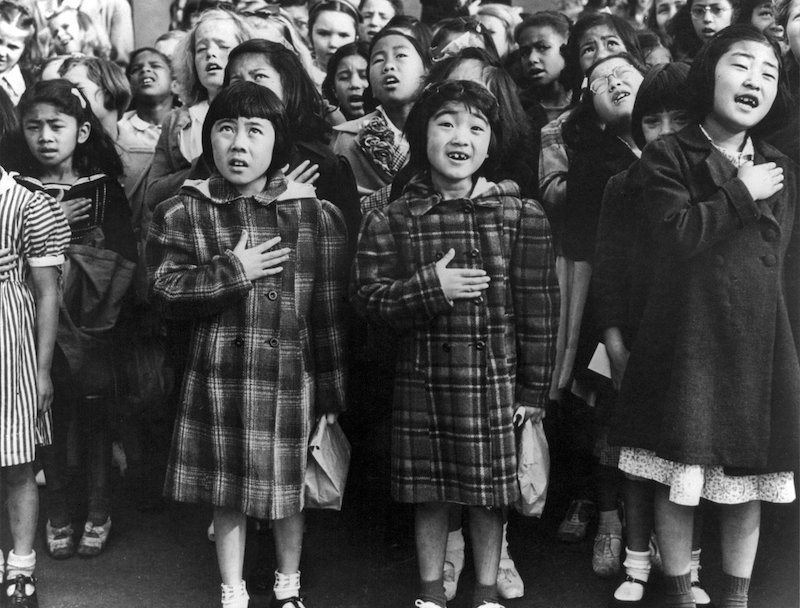

Photo: Dorothea Lange, 1942 (public domain)

Photo: Dorothea Lange, 1942 (public domain)

Mickey Z. -- World News Trust

June 25, 2018

More than just a “good war,” former NBC newsman and renowned The Greatest Generation author Tom Brokaw deemed World War II “the greatest war the world has seen.” But what corporate media shills like Brokaw tend to omit is that the United States fought that war against racism with a segregated army.

It fought the war to end atrocities by participating in the shooting of surrendering soldiers, the starvation of POWs, the deliberate bombing of civilians, wiping out hospitals, strafing lifeboats, and in the Pacific boiling flesh off enemy skulls to make table ornaments for sweethearts.

And Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the leader of this alleged anti-racist, anti-atrocity force, signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, interning over 100,000 Japanese-Americans -- including babies and young children -- without due process. Thus, in the name of taking on the architects of German prison camps, he became the architect of American prison camps.

We know what those “free world” prison camps were like thank, in part, to the committed and essential work of photographer Dorothea Lange.

Dust Bowl

Born in 1895 in New Jersey, Dorothea Margaretta Nutzhorn became Dorothea Lange (assuming her mother’s maiden name) at age 12, when her father walked out on the family.

Lange went on to study photography at Columbia University before moving to San Francisco to open a successful portrait studio. But along came the Great Depression. Lange took her camera to the streets to document the lives of unemployed and homeless people. This, in turn, led to her employment with the federal Resettlement Administration (RA), later called the Farm Security Administration (FSA).

Working with the RA and FSA from 1935 to 1939, Lange connected with and took photos of migrant workers, displaced farm families, and sharecroppers -- iconic photos that were distributed free to newspapers all across America.

Executive Order 9066

Through her work in the Dust Bowl, Lange was familiar with images of displacement. When she was hired by the War Relocation Authority to document life in Japanese neighborhoods, processing centers, and internment camp facilities, the racial and civil rights issues added a new dimension to her growing body of work.

“What was horrifying was to do this thing completely on the basis of what blood may be coursing through a person’s veins, nothing else. Nothing to do with your affiliations or friendships or associations. Just blood,” Lange said.

As the Library of Congress wrote, “Lange quickly found herself at odds with her employer and her subjects’ persecutors, the United States government.”

“Lange’s attempts to use her camera to expose the social impact of the mass incarcerations came into conflict with the authorities,” says journalist, Richard Phillips. “She was regarded with suspicion by the military, and even called before the War Relocation Authority on two occasions for alleged misuse of her photographs. The Wartime Civil Control Agency impounded most of her internment photographs, refusing to release them until after the war.”

True to her belief that her lens could teach people “how to see without a camera,” Lange created images of human dignity and courage in the face of vast injustice. But it wouldn’t be until seven years after her death that her Japanese internment camp work would finally reach a wide audience.

In 1972, the Whitney Museum incorporated twenty-seven of Lange’s images into an exhibit called “Executive Order 9066.” New York Times critic A.D. Coleman subsequently called Lange’s photographs “documents of such a high order that they convey the feelings of the victims as well as the facts of the crime.”

In the phallocentric world of photographic art, of course, Dorothea Lange has never received the legendary status she deserves. But let it be known: She recognized injustice. She helped others to see and understand it. She was willing to defy authority to make all this happen.

Mickey Z. is the founder of Helping Homeless Women - NYC, offering direct relief to women on the streets of New York City. To help him grow this project, CLICK HERE and make a donation right now. And please spread the word!