In this first chapter, as elsewhere in our text, Lévi covers a great deal in a small number of pages and makes few allowances for those who like their instruction cut up into bite-sized pieces. Let’s take it one step at at time.

To begin with, we encounter René Descartes’ famous dictum, “I think, therefore I am.” That bit of prose has been misunderstood considerably in recent years, so it’s helptul to review its meaning here. Descartes in his philosophical reflections was trying to find something he could not doubt, which he could then use as a foundation for philosophy. It occurred to him that the fact that he was doubting implied that there had to be a René Descartes to do the doubting, and so he had his foundation: his own experience of himself as a conscious, reflecting, individual being. That was the birth certificate of modern philosophy, and the entire trajectory of modern Western philosophical thought from Descartes to Deleuze traces out the way that this core idea was explored, developed, challenged, affirmed, rejected, reframed, and eventually reduced to self-negating gibberish.

Lévi chose a different approach. The divine name that the God of Israel revealed to Moses in the Book of Exodus was אהיה אשר אהיה , Ehyeh asher Ehyeh, “I am that I am.” Lévi applies the same principle more generally: being is being, what exists is what exists. More formally, what you experience exists as an experience, whatever other modes of existence may be hypothesized for it. The basic formula of existentialism -- “existence precedes essence” -- could almost be Lévi’s formula as well, though he refuses to predicate anything of experience besides the simple fact that it happens, and he doesn’t mope, as the existentialists did, because experience refuses to provide him with the certainties they pined for.

And thought, the form of experience that Descartes took as his standpoint? Thought is the word, le verbe, which Mark and I agreed to translate as “the verb” to catch both the meanings of the French word. Less tersely, thought is speech, the net of language in which we try however clumsily to catch what exists. It is always secondary to, and dependent on, the primary reality of experience. When Descartes used the net in an attempt to prove the existence of fish -- well, the joke is inescapable: he put Descartes before the horse. The fact that there was definitely an experience being had didn’t prove that some essentially René Descartesish entity was having it, and it certainly didn’t justify the grandiose edifice he built atop that shaky foundation.

Like Descartes, you experience yourself as a center of will, thought, feeling, perception, and that experience exists, as an experience. That doesn’t prove that there’s a “you” separate from that experience, though of course it doesn’t disprove it either. Drawing sweeping conclusions from that experience, of a kind that are not drawn from other experiences -- as Descartes did, and as a great many modern Western philosophers did in his wake -- is a dubious procedure at best, and its results were tolerably often just as dubious. It took Nietzsche’s furious prose to bring philosophy back face to face with the raw data of experience. The encounter was traumatic enough that a great many philosophers are still hiding in their closets waiting for the big bad universe to go away and leave them in peace.

Long before Nietzsche, however, Lévi was already proposing a reliance on experience as such as the philosophical basis for his system of magic. Why does magic need a philosophical basis? Because magic is to philosophy what engineering is to science; it is applied or operative philosophy. It works, as we’ll see, with the irrational aspects of the human mind primarily, but in what Lévi calls high magic those aspects are always guided and directed by a clear conscious understanding of principles. Folk magic, like folk crafts, uses traditional rules of thumb to guide practice; magic, like engineering, uses a conceptual understanding instead.

Experience, as we have noted, includes the experience of self -- of yourself as a center of will, thought, feeling, and perception. All other experiences you have relate in one way or another to the collection of experiences that you sum up in the capacious word “me.” What is this collection of experiences? That’s the next theme of this chapter.

Who are you? If you take up magic you will have to confront that question over and over again. Knowing your strengths and weaknesses, your desires and aversions, your passions and prejudices is essential to the successful practice of magic. To be a mage is to be a priest and a king, Lévi says, a priest invoking the astral light and a king over the realities that unfold from that light. If you follow the path of magic you must be prepared to act as a priest and a king (or, we can add, as a priestess and a queen). You will not be ruling over other people, by the way. Your first task is to rule over yourself; your second is to rule over the astral light, the great magical agent to which Lévi devotes many pages to come.

The great obstacle to that priesthood and kingship is slavery to passions and prejudices. By passions are meant instinctive drives, the whole range of cravings and aversions we inherit from the biological ancestors of our species, subject to modification by cultural and personal factors. By prejudices are meant, as the word literally means, pre-judgments, fixed ideas borrowed from our cultures or created by ourselves. We all have passions and prejudices, and Lévi does not pretend that we can get rid of them. It is simply a question of who will be the master.

Now of course this sort of thinking is unfashionable in some circles nowadays, just as they were unfashionable in some circles in Lévi’s time. Romanticism was a waning current by the time he wrote, but there were still plenty of people in Parisian literary and cultural circles who preached the doctrine of wallowing in passion, abandoning reflection, and casting off the oh-so-dreary burden of self-control and self-knowledge. Some of those people dabbled in magic -- as of course some of their equivalents still do the same thing today.

Nowadays there are influential cultural trends and schools of thought, with their own ornate philosophical volumes to back them up, insisting that self-control is bad, self-mastery is bad, you should let go of all those bourgeois hangups and abandon yourself to the churning abyss of passion, and so on. If you’re interested in looking, you can find entire volumes insisting that schizophrenia is good and sanity is bad, and this sort of thinking has its echoes in some corners of the magical scene. If your idea of the zenith of human potential involves rocking back and forth in a puddle of your own urine while babbling nonsense syllables, don’t let me stop you, but, er, that’s not what Eliphas Lévi is interested in teaching.

Lévi makes a strict distinction here, and it’s one worth making. To attain conscious control over your passions and your prejudices is to be able to participate freely in the dance of magical forces. To remain subject to your passions and your prejudices is to be a plaything of those forces, and they are careless of their toys. Those are your choices; take your pick.

Granting for a moment that you’ve chosen the path of high magic, what then? Lévi offers you four disciplines, the four classic magical virtues: to know, to dare, to will, and to be silent. Aspirants to magical power must replace their ignorance with knowledge, their timidity with daring, their passivity with will, and their thoughtless chatter with silence: not just once, in some formal or symbolic sense, but continually, whenever appropriate opportunities presents themselves. This is the most basic and most essential practice of magical training, and it can be carried out in every part of daily life.

As he presents this course of study, Lévi goes deeper into theory. Magic, he says, is the traditional science of the secrets of nature that comes to us from the mages; that is to say, magic isn’t whatever you want it to be; it is a specific body of traditional knowledge that reached Lévi’s time from a specific source. (“Science,” remember, still meant any body of organized knowledge, not just modern science, when Lévi wrote.) The only doctrine of magic is that the visible is a manifestation of the invisible; that is to say, the traditions of magic hold that the world is not an illusion or a lie, that what we experience is in some sense analogous to underlying realities we do not experience. (Ehyeh asher Ehyeh, what exists is what exists.)

Thus our intellects and our wills are not left tumbling about in a void. The discoveries of the mages of the past are a source of guidance here and now, and the experiences with which we interact are analogous to a deeper reality, unknowable but present. Furthermore, we have another power as potent as these two. That power received very little attention from the popular and educated cultures of Lévi’s time. It gets more lip service these days, but its power and potential are still generally neglected. That power is the imagination, which Lévi also called the diaphane and the translucent.

The discovery of the imagination is one of the great achievements of the 19th century. Go looking in books on psychology older than that and you’ll find that the mind’s image-making power is usually neglected, or lumped in with one of the other mental functions. The Romantic movement as the end of the 18th century opened the way to a recognition of imagination as a core power of the mind; by the middle of the nineteenth, writers such as Lévi embraced it; by the end of the century fantasy fiction, the great literary expression of imagination unbound, had been invented by William Morris, and the world began to change accordingly. In Lévi’s time the imagination was still little regarded, and so he had to spend paragraphs explaining such basic points as the fact that the way you imagine yourself plays a potent role in shaping your experiences in life.

The words “diaphane” and “translucent,” by the way, both mean the same thing: something through which light can pass. In this turn of phrase is an essential key to Lévi’s approach, though this chapter does not yet present the lock that the key can open. The imagination, rightly used, is the capacity to create forms through which the light of understanding can pass. It is the third factor that resolves a binary that got a lot of attention in Lévi’s book, and at least as much attention in his time: the binary between faith and reason.

Lévi’s approach to this binary, which we’ll be discussing repeatedly from different angles as these essays proceed, is as straightforward as it is practical. There are things that we are capable of knowing by applying reason to our experiences, he suggests, and there are things that we can’t know by that means. Mages, like everyone else, deal with both kinds of things on a daily basis. Being mages, they do so in a thoughtful and deliberate manner, and respond to each of these categories of things with a human capacity suited to it. Those things that can be known are properly addressed through reason; those things that cannot be known are properly addressed through faith. Applying faith to the proper objects of reason, or reason to the proper objects of faith, is to Lévi the basic formula of human confusion.

It’s important in this context to understand what Lévi means by faith. He doesn’t mean belief in doctrines. (This will become extremely clear as we proceed.) He means an attitude of trust in traditional practices and the myths that frame them. As a Catholic, Lévi attended Mass and accepted that there was a truth of some kind behind the mythic images and ritual practices of his religion. That was enough for him, and from his point of view, it was a profound mistake for religious authorities to go beyond that and try to make dogmatic claims about what was and was not true about the universe. That was trying to apply faith to the proper objects of reason -- trying to claim to know about things that human beings can’t know.

Equally, when rationalists denounced religion root and branch and insisted that traditional rituals and myths should be discarded because they weren’t rational, they were trying to apply reason to the proper objects of faith, an equally unhelpful act. To apply reason to the things we can know something about and faith to those things that are beyond the reach of the human mind: that was his formula for a working reconciliation between science and religion, reason and faith.

Imagination is central to that reconciliation. Myths and rituals are creations and vehicles of the human imagination, which enables us to approach in symbolic form those aspects of the cosmos we can’t understand in any other way. As the diaphane, the imagination establishes forms through which light can pass. How this is done will be made clearer as we proceed.

Notes for Study and Practice:

It’s quite possible to get a great deal out of The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic by the simple expedient of reading each chapter several times and thinking at length about the ideas and imagery that Lévi presents. For those who want to push things a little further, however, meditation is a classic tool for doing so.

The method of meditation I will be teaching as we read Lévi is one that is implicit in his text, and was developed in various ways by later occultists following in his footsteps. It is a simple and very safe method, suitable for complete beginners but not without benefits for more experienced practitioners. It will take you five minutes a day. Its requirements are a comfortable chair, your copy of Lévi’s book, and a tarot deck of one of the varieties discussed earlier.

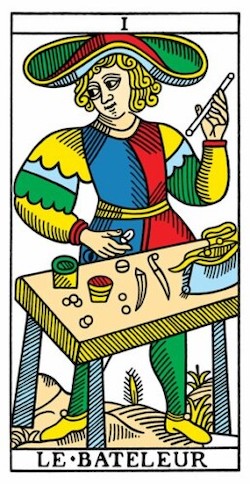

For your work on this chapter, take Trump I, Le Bateleur -- this translates as “The Juggler” or “The Magician.” Your first task is to study it and get familiar with the imagery. Sit down, get out the card, and study it. Spend five minutes doing this on the first day you devote to this practice.

Your second task is to associate a letter with it. Lévi gives you two options, the Hebrew letter א (Aleph) or the Latin letter A. Choose one alphabet and stick to it. The sound values aren’t of any importance here, nor is there a “right” choice. You’re choosing labels for a mental filing cabinet. Most people can make the necessary association quite promptly, but spend a session exploring it. Sit down, get out the card, and study it. Whichever letter you choose, how does it relate to the card? Many decks make the figure on this cart stand in a posture representing Aleph, but don’t stop with that. See how many modes of Aleph-ness or A-ness you can find in your card.

The third, fourth, and fifth sessions are devoted to the three titles Lévi gives for the card: Disciplina, Ain Soph, Kether. Sit down, get out the card, and study it. How does discipline relate to the imagery on the card and the letter you’ve chosen? That’s one session. How about the Cabalistic concept of Ain Soph? Or the concept of Kether the Crown, the first sphere of the Tree of Life? Those are the next two. (If you have no previous knowledge about the Cabala, do a little reading online; you just need to have a basic notion of what these terms mean.)

One of the great booby traps awaiting inexperienced occultists inevitably pops up at this point: “But what if I get the wrong answer?” There are no wrong answers in meditation. Seriously, there are no wrong answers in meditation. Your goal is to learn how to work with certain capacities of will and imagination most people never develop. Stray thoughts, strange fancies, and whimsical notions do this as well as anything.

Sessions Six through the end of the month are done exactly the same way, except that you take the concepts from the chapter. Sit down, get out the card, and study it. Then open the book to Chapter I of the Doctrine and find something in it that interests you. Spend five minutes figuring out how it relates to the imagery on the card, the letter, and the three titles. Do the same thing with a different passage the next day, and the day after, and so on.

Don’t worry about where this is going. Unless you’ve already done this kind of practice, the goal won’t make any kind of sense to you. Just do the practice. You’ll find, if you stick with it, that over time the card you’re working on takes on a curious quality I can only call conceptual three-dimensionality: a depth is present that was not there before, a depth of meaning and ideation. It can be very subtle or very loud, or anything in between. Don’t sense it? Don’t worry. Sit down, get out the card, and study it. Do the practice and see where it takes you.

We’ll be going on to “Chapter 2: The Columns of the Temple” on July 14, 2021. See you then!

***

John Michael Greer is a widely read author, blogger, and astrologer whose work focuses on the overlaps between ecology, spirituality, and the future of industrial society. He served twelve years as Grand Archdruid of the Ancient Order of Druids in America, and remains active in that order as well as several other branches of Druid nature spirituality. He currently lives in East Providence, Rhode Island, with his wife Sara.